Love & Rockets

Season 13 Episode 1 | 56m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

A self-published comic book made by brothers from Oxnard, Ca. makes comic book history.

In 1981, Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez wrote "Love and Rockets #1," a self-published comic book edited by their brother Mario. They sold that first issue at conventions for a dollar apiece and submitted it to be reviewed at The Comics Journal. Instead, Gary Groth, offered to republish it through Fantagaphics Books. The brothers accepted and made graphic novel publishing history.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Artbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal

Love & Rockets

Season 13 Episode 1 | 56m 43sVideo has Closed Captions

In 1981, Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez wrote "Love and Rockets #1," a self-published comic book edited by their brother Mario. They sold that first issue at conventions for a dollar apiece and submitted it to be reviewed at The Comics Journal. Instead, Gary Groth, offered to republish it through Fantagaphics Books. The brothers accepted and made graphic novel publishing history.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Artbound

Artbound is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[Punk rock playing] Justin Hall: "Love and Rockets" is actually the closest thing we have to the "Great American Comic Book."

Esther Claudio Moreno: They created this beautiful mix between fantasy and reality that nobody was doing before.

♪ Carolina Miranda: This is a consistent series written and drawn by the two same artists over a period of 40 years.

[Funk music playing] ♪ Announcer: This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill philanthropy; the Los Angeles County Department of Arts & Culture; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Frieda Berlinski Foundation; and the National Endowment for the Arts, on the web at arts.gov.

♪ Katie Skelly: Hello.

My name is Katie Skelly.

I am the co-host of the "Thick Lines Podcast," and I have a very special episode for our listeners today with special guests Jaime Hernandez and Gilbert Hernandez.

Thank you so much for joining.

♪ Did you guys discuss that feeling that you were both having that, you know, you were sort of doing the best work but not getting recognition at this time?

Did you discuss that between yourselves?

Jaime: Sometimes there was whining, but--no.

When we would go out and do shows, it was just, like, "This is for the fans," the fans that still liked us, and we like our fans and stuff.

I mean, if it was just me and him on the phone, we would every once in a while.

Skelly: Gilbert, did you speak to Jaime about that?

Gilbert: We would complain, but really, you know, and then once we stopped complaining, back to the board.

Skelly: Right.

Gilbert: You know, there was never any pauses or any feelings of giving up or anything like that, never ever crossed our minds because then what would we do, you know?

This is what we do.

This is who we are, you know, so-- ♪ Miranda: What is "Love and Rockets" about?

How much time do you have?

I think the first word that comes to mind is "epic."

Frederick Luis Aldama: "Love and Rockets" is the umbrella for stories created originally by 3 brothers--Mario, Gilbert, and Jaime, each following their own drumbeat, their own style, their own characters.

Miranda: That have unfolded over 4 decades tracing the lives of several key characters and the characters that orbit around them.

Kovinick Hernandez: It's about real people, and it's just about family and life and relationships.

Moreno: They amplify the voices of the Latinx community, of women, of LGBTQ community and with very complex characters and not only that.

They have aged their characters throughout the years, throughout decades, and they were not afraid to get into the complexities of life, and their characters got different problems.

They've got problems with their bodies.

They've got problems with loss, with death, with everything that is universal.

Hall: "Love and Rockets" is actually about the movement of time and how that affects characters, individual characters, how it affects families, how it affects culture and community.

Moreno: There is no universe as complex as this one that has evolved in time in such a way.

Aldama: Love, amor, right--the heart, the person, the interpersonal--and then the rockets--the technology, the sci-fi, the mixing of both the personal, the everyday, the characters' slice of life, and then something extraordinary, as well.

♪ Miranda: The best way to describe "Love and Rockets," or the easiest way, is that there's two universes.

There is the universe created by Gilbert which, to a large degree, inhabits this fictional Latin American town of Palomar, and the central character is Luba, who is this somewhat taciturn, matriarchal, stubborn figure who kind of runs her community in literal and both figurative ways, and then you have Locas.

I think of that as the Maggie and Hopey stories.

That's Jaime's world.

That's the world he's created.

That, the bulk of it takes place in Hoppers, or Huerta, which is a stand-in for Oxnard oftentimes, again, this fictional place that evokes L.A. at this specific period in time, if you think of, like, late Seventies, early Eighties, the early roots of the punk movement, or crazy concerts in warehouses and bands sleeping in squats.

Those are the two large universes that they've created.

Eric Reynolds: Started out as a kind of half sci-fi, half domestic drama.

The "Rockets" part of "Love and Rockets" went away pretty quickly and became just this story about these young people in Los Angeles.

♪ Jaime: It came naturally while I was learning.

"How do I make this panel work more?

Maybe if she's leaning this way, maybe that kind of tells you something about her attitude."

It's how they're leaning, how they're standing on the Earth.

♪ Miranda: Some of the themes that emerge in their comics, certainly the fact that it depicts Latino L.A., the ways on which it draws from, like, folklore, magical realism, punk, the city's geography is so unique and so singular, and it serves, in a way, as a document of our city at a particular place in time.

Hall: It's been serialized since the early 1980s.

During this time period, the casts of characters have expanded, and we've seen them go through different generations and tackling different issues as American life has changed over this time period, so it's a monumental work.

Reynolds: There's an alchemy to the way these stories flow and riff off of each other.

It's something innate in them either by virtue of the fact that they're brothers.

They're both individually great and would be great on their own, but taken collectively, "Love and Rockets" is just such a singular series, greater than the sum of its parts.

♪ Jaime: My mother was from a little town outside El Paso, Texas, and my dad was from Chihuahua, Mexico, but they didn't meet till they got to Oxnard, and they were both, like, farm workers and worked at the packing houses and stuff like that, and they met in the Forties.

They got married and had 6 kids.

I was the fourth in line.

Growing up in Oxnard was pretty average.

It was a very small town.

We grew up in a house with comics.

Our oldest brother Mario started collecting them because Mom encouraged him.

Gilbert: And the more comics that came in the house, she was fine with it.

She would read them, too, because she liked them, and Mario was fascinated by the artwork and the covers.

He thought this was just interesting, so, like, he would get more because, remember, in those days, I mean, comic books were a dime, and we had all kinds of comic books that were coming out from the early Sixties.

Whatever was out there, he would buy.

Aldama: And they'd been reading, you know, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko comics, Spidey and Fantastic Four.

♪ Jamie: But it was the comic books that Owen Fitzgerald and Al Wiseman drew that I was really drawn to.

Here is "Dennis the Menace," by Owen Fitzgerald.

He did a giant Christmas issue down back in '61.

Owen Fitzgerald was just a master at cartooning, which is a lot different than illustration.

His cartooning brings it to life.

It wasn't just one single panel.

It was comics flowing.

"Wishbone Thinking," this was the one where Dennis, he wins the wishbone, and he's on his way to the North Pole, and they're like, "No, no, no, no.

You can't go to the North Pole."

"Why can't I?

What's the North Pole like?"

She's going, "It's time for bed."

She's scooting him upstairs.

Then she's giving him a bath.

Then she's drying him off.

Then she's putting on his sleepers, and then she's putting her to bed, and the whole time, she's explaining what the North Pole is like, and as a kid, I just knew this.

This is real.

These comics are home.

I just can feel my mom in this.

I can feel me there, and I remember going, "I don't see this in a Marvel comic.

I don't see this in other comics."

It's just I'm seeing my mom do this stuff, you know.

If I want to make my characters as human as possible, I'm gonna use these tricks because he knows how to do it.

♪ Gilbert: Well, this is the big fella.

This is the guy that inspired me to be who I am, what kind of stories that Palomar were based on, how did I want to draw them, how did I want to present my comics, and it was a guy named Bob Bolling, and at Archie, he was given the task to draw "Little Archie" because "Dennis the Menace" comics were so popular that he could just do whatever he wanted in "Little Archie."

I mean, you know, "Just keep it clean and do your own stories," but what was going on and what really brought me to Bob Bolling as my hero, like, look at this first panel.

It's completely silent, and they're looking for the aliens that he claims that were there, and his mom's going, "There's no aliens.

There's no--" and she says, "See?

Everything's--" She just thinks he fixed his room, but the aliens did it, so anyway, in the third panel, she's going, "Oh, it's chilly in here."

She walks out, and then they see a shooting star, and he knows it's the aliens, and she just thinks it's good luck, but he's, you know--anyway, just these little, tiny scenes that Bolling could do.

Gilbert and Mario, being the oldest, they decided to draw their own comics, but they didn't really know how to tell a story, so it was kind of fun through a kid's eyes that they would just draw weird images or whatever and try to create their own characters, you know.

Aldama: Perfecting their art, in many ways, in and through mainstream comics and the art of bringing energy into two-dimensional space, into two-dimensional characters, things that explode, characters through posture and gesture, right, mainstream superhero comics.

For the bros, it became their art school.

Gilbert: We learned to love the medium because we liked almost every subject that they put out in a comic.

Here's one of the few comics I kept from when I drew as a kid.

Most of them are gone, but this one's from 1968 and "Rocket Comics," and it has Batman, the Puppet, the Rocket, the Hulk, and, yes, it's very interesting, "The Puppet Versus The Rocket."

See, it's not very good, and I was way ahead of my time.

Here's "Superman Versus The Hulk."

Look at this lousy art.

Well, I was only a kid.

At the time, I was super into Marvel, and Superman, I just made him an arrogant character like, "Oh, he's gonna beat up the Hulk, and it's gonna be easy," but then the Hulk starts beating him up, and Superman's worried, and so anyway, Superman buries him in a bunch of rocks, and Hulk escapes, but I had Superman with black--his eyes are blackened because the Hulk was kicking his butt.

Jaime: It started because Dad wanted to shut us up, and instead of sticking us in front of the TV, he would cut up a grocery bag.

He would lay it out, give us crayons, and go, "Paint."

Gilbert: Mario and I would draw together, and then Jaime, who was little, he would see us drawing, goes, "Oh, well, maybe I better draw comics, too," you know.

Little did we know, so-- ♪ Jaime: I was really into it.

I didn't know why, but I thought drawing was cool, you know?

♪ This cover, it just shows life, you know.

Like, I can picture where I got this house, this setting from my old neighborhood.

You know, there was no fence, but there was a clothesline in their yard.

I remember.

This is on Wolff Street.

Yeah.

Ha ha!

Anyway, and then you have the kids just running through, and it's all the kids in the neighborhood, even the kids I didn't hang out with a lot.

To me, it's home, you know.

It just gives you a feeling that this is how people live.

This is how my characters live.

Hall: "Love and Rockets" has been absolutely seminal in depicting race and ethnicity in American comics not only in terms of the way that they write their stories and really creating authentic stories coming from different perspectives, but also visually, and it's really quite remarkable because they do most of their work in black-and-white, so they don't directly show skin tone.

However, the way that they're so good at crafting the different details of face and body related to different ethnicities and cultures and races that you really come away with an incredibly profound understanding of the racial diversity of their stories.

Miranda: Asian characters, Black characters, Afro Latino characters will materialize now and again and in ways that are not expository.

♪ Gilbert: The focus was on creating Latino characters because, you know, growing up, you get snatches of racism and the complete neglect of people of color, mostly on TV and, you know, movies, as well.

Even as a kid, there's great people I know--cousins, friends, aunts and uncles, adults--and they're so colorful in an enriching way, very familial way that I go, "Why isn't this represented?"

♪ Whereas Palomar was more specific--there were brown people, and they were living in another country, and they had their own way of living; it was separate from the U.S.--I knew that would be a little bit difficult for some American readers, but I thought if I kept at it, they would get it because it takes a while for people to get new things, so that's why I created Palomar, took me a while to do it, and luckily, the response was good for it, not great.

It was good.

Reynolds: Palomar in the early years, the central character was Luba, in some ways still is, but it was really Palomar that was, I think, the central character.

♪ Gilbert: So I decided just, well, I could tell stories that I heard when I was a kid or similar, you know?

I could do stories about my family.

For me, it just spoke to the world with my comics.

This is the earliest drawings of the Palomar characters, appeared in "Love and Rockets"--Pipo, Carmen, and Luba and the boys.

This is a scene that I used in the first Palomar story.

Of course, it's changed a lot, but it pretty much showed the things I wanted to show in my comics.

I wanted to be different from what was, you know, in regular mainstream comics.

Here's the earliest imagery of Luba as the washerwoman of Palomar.

♪ I start from the head just because I've always drawn that way, so she's not old at all, maybe 30ish or whatever, but I would put lines on her face just to--you know, just looking older than she is.

She's got thin arms, got to always remember that.

She's not that curvy.

She's very, actually, pretty narrow, kind of boxy.

Oh, you got to remember the hammer.

♪ Reynolds: Gilbert told some incredibly ambitious and sophisticated stories and eventually, I think, kind of exhausted Palomar from his point of view to the point where he needed to expand their horizons a little bit, so one of the big differences that's happened in the series over the last--I don't know--10, 15 years is, many of the characters have moved to the United States and now live in Los Angeles, these Central American characters, and effectively making them immigrants in the United States suddenly thrust into U.S. culture, I think, was really affecting in terms of highlighting for the readers, you know, the kind of immigrant experience, probably even more resonant now ♪ Miranda: Always thought of their comic books as having this very distinctive Los Angeles feel.

A lot of times, you don't know that they're in Southern California.

They never say they're in Southern California, but there are these architectural cues that give it away, and I think this story probably does it more than most, you know--the scratchy graffiti with the "Loco 87" written right here as probably Jaime's way of signing the book, some of the fashion--but certainly street scenes, this incredible street scene that shows people hanging out with the lowriders and the cholas and homegirls and the style, the slicked-back hair, this could exist nowhere else.

This is Los Angeles.

Even if it's never articulated as Los Angeles, it just has the feel, all of the visual signifiers of the city.

Moreno: And, like, seeing Hoppers and the adventures of Hopey and Maggie, and I was like, "Ah, OK. L.A. is "Amor y Cohetes."

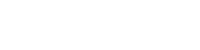

[Punk rock playing] Gilbert: Once you get older, especially teenagers, if they're living in a quiet community, they tend to get restless, so we were very restless and very, very like, "Ohh, I got to get out of here.

I got to do something," you know, and so that's how we gravitated toward punk rock music, because it was more alive and it was more-- seemed like something bigger was happening than in our little, small town, so we gravitated toward that.

Jaime: And it was kind of like, "OK. Now you can live rock and roll," because you got to go see the band and you're in the same space as them.

Kovinick Hernandez: I actually saw Gilbert at a record store once.

This is 19--late '78, so he had short hair.

He was wearing straight-leg pants, the button-up shirt with the small collar, and then he had a Blondie button on, so that was like, "Oh, wow.

He knows something," so it was just a couple weeks later when we went to see The Clash for the first time and on their first tour of the U.S., and they played at the Santa Monica Civic, and we actually saw a girl that we recognized that had gone to our high school, so after the show, we ran over to talk to her and say, like, "Oh, my God, I can't believe, you know, somebody from Hueneme High School is here," and she said, "Yeah.

I'm here with my cousins," and she pointed.

There was a row of 4 guys standing there, and it was Gilbert, Jaime, Ishmael, and Richie, so 4 of the brothers, and I recognized Gilbert, and I go, "That's the guy I saw at the record store," so we started hanging out with them, you know, and we'd just go to see bands in L.A. and hang out.

♪ Jaime: Hey, we're in L.A.'s Chinatown.

Behind us is what was the world-famous Hong Kong Cafe, right... Gilbert: Right.

Jaime: and where we saw a lot of punk bands upstairs Gilbert: Yeah.

We saw a lot of the early classic punk bands from Los Angeles.

You know, if they weren't opening up for a bigger band from another country or city, they would play here, and they would--their own audience.

Jaime: We saw Black Flag, The Germs, The Plugz, The Bags.

I saw The Bags, saw The Zero's, saw The Weirdos.

We hadn't started "Love and Rockets" yet, but it was there.

Like, my characters that I was planning to do all started wearing punk clothes, you know, and I always like to make it authentic, and I just started teaching myself this stuff over the years, and my character Maggie kept growing up looking different.

I was like, "Well, I'll make her dress like punk because I know punk.

I know punk fashion," so I started to give her punk clothes.

I cut her hair short.

I gave her spiky hair.

I gave her straight-leg pants.

I gave her cool boots, you know.

I just thought, you know, "Well, just draw what you know."

I don't see that when people do rock and roll and stuff.

They're always just following the band, like, the band onstage.

OK.

I did that here, but at the same time, I tried to capture that you're the audience in the show because that's how I witnessed punk and rock and roll, was, I was in the audience most of the time.

I didn't really have a set plan for comics, so it was easy to just draw whatever I wanted to.

I wasn't going anywhere with it.

I wasn't selling it at anything.

Kovinick Hernandez: The punk scene was about being yourself, being creative, and doing what you want to do, so their making a comic seemed very natural.

Jaime: Gilbert and I were still bumming around the house, and Mario goes, "What's all this?

What's this you guys have been doing?"

and I was like, "Oh, we're just drawing comics because one day, we hope this will be published somewhere," and then Mario just goes, "Why don't we do our own?"

and Gilbert and I were like, "OK." Gilbert: Well, I had stuff laying around because I was kind of jaded.

I was like, "I'm just doing this for nothing, making these comics for nothing."

They were just, you know, my own thing, and I was doing "BEM"... ♪ and I just let it sit there for, like, 6 months because, like, you know, it was unfinished.

Jaime: And I remember they said, since I was still the youngest one, they were like, "OK, Jaime.

We need about 13 pages from you," and I go, "OK.

Uh, what do I got?

What do I got?

I got Maggie.

I got Hopey.

I got Maggie's bass mechanic.

Uh, I got these other characters," and I just started to throw them all together in these stories.

That's how my stuff started, you know.

Gilbert was more focused because he had more work done.

You know, he had learned how to structure a story before I did.

I was still learning along the way.

♪ Gilbert: When Mario and I finally saw the work that Jaime was gonna put in the comic book, we were astonished.

We didn't know he drew that well.

Jaime was always a very good artist, but he went to college, and he took a life-drawing class, and he learned on his own to draw the way he wanted to draw.

We looked at it, we went, "Holy ..., this is really good.

This is really something," so we knew right away, like, this art's gonna sell this comic or get it noticed.

Jaime: Gilbert was doing sketches of covers, like, what would the cover be, and then he was thinking about what will the title be.

Gilbert: One of the titles was "Robots and Romance," but that was too niche.

That was too close to a goofy science fiction thing, so when I softened it up with "love" and then put the "rockets" as the hard edge, it just worked together.

Jaime: And me and Mario just looked at "Love and Rockets," and we just go, "Oh, that's the one."

♪ Gilbert: We borrowed $700 from our little brother Ismael-- ha ha!--and we had it, got it printed, and we had to fold them ourselves, each page, because it was too expensive to have them collate them and staple them, so we just had all these sheets, and we just put them together in Mario's living room, you know, and then he had this long stapler, you know, to staple them that we had to borrow.

Jaime: But I remember the first issue we put together, we had it in our hands, and I remember we were at my mom's house, and we put-- we, like, propped it up on the couch, and then we just sat in the living room and just looked at it--ha ha!-- you know, like, "Hey, that's a comic.

We made a comic."

♪ Gilbert: It was just to be a fanzine for us to do and, hopefully, people will like.

"Oh, this was a cool fanzine."

That's as far as we thought about it.

Ah, and here we have the first self-published issue of "Love and Rockets."

I just decided to do the cover this way because I just wanted the comic to look mysterious.

It turned out to be too mysterious because nobody knew what was going on.

They didn't understand.

This story, "BEM," I was just-- I have a great-- I'm really grossed out by snails, so I'll draw things that gross me out just so I can get over that, so here I have snails on the wall and, like I said, just to be mysterious.

There was no real deep meaning for any of this, and, you know, I like monster movies, so I'm gonna have a giant monster that it's-- you know, that people are worried about in the world and villains and this and that, and here, interestingly enough, this is the first time I used Luba, and she was just supposed to be a character in this story, and she turned out to be a lot more interesting because of her attitude and all that.

So, you know, you'll see Luba on these pages.

Reynolds: The first thing you recognize in the very first issue of "Love and Rockets" is that they hadn't even really dialed in on where they were going with it.

Gilbert's first story is a more traditional sci-fi narrative than he would go on to do over the next 10 years and so is Jaime's, but you can still see from this very first page "Mechanix starring Maggie, Race, and Hopey."

They're there and they're already fairly real, fully realized characters, even though they're existing in this kind of more sci-fi milieu with these hover scooters.

Right from the get-go you can just see Jaime's sense of composition and craft is there.

His line work, his what we would call inking, laying ink by a pen or brush over the pencil drawings.

He's got a control that's pretty phenomenal for what was basically, you know, an 18-, 19-, 20-year-old.

If you look at this explosion here, just beautifully composed and executed.

Gilbert: But the skill level that Jaime brought to it and just the simple, like, readability and enjoyment of reading a comic was really in Jaime's stories.

It was even a surprise to me how good this turned out.

You know, more stuff from Jaime that--just experimental and it was because we had no place to fall.

We just--it was we could do what we wanted and whatever inspired us.

♪ Aldama: Mario's, you know, older brother, married, family and economic pressures much earlier than Gilbert and Jaime had right in their lives.

So, at a certain moment, he did have to kind of step away from "Love and Rockets."

So, we see a lot of Mario in those, you know, first 5, 6, 7 years of "Love and Rockets" especially, and then just circumstance, I think, is what really led to Mario kind of pulling out and, you know, having to get, you know, a job and take care of family and not being able to go down that route that Gilbert and Jaime, and he's a great storyteller.

He's also a great comic book creator.

Very different style.

And Gilbert and Jaime, as a very unusual situation, make a living exclusively through comics and illustration work.

You know, that's very unusual, as many of us know.

♪ Jaime: And so, we were kind of desperate.

Like, OK, how do we sell it?

How to-- and to me it wasn't about being rich, it was more about, like, if people like this, I get to do this for forever, you know?

Gilbert: But the comic gave us something to do, to focus on, and to express ourselves.

♪ Jaime: We were reading the critical magazine "The Comics Journal," and we kind of liked their cockiness and their bold journalism, trashing Marvel Comics and stuff like that.

"Comics Journal" was run by Gary Groth and Kim Thompson.

Groth: I co-founded "The Comics Journal" in 1976.

It started as a adversarial magazine about the comics industry.

And what we wanted to do was to publish real criticism and see how comics could stand up to that.

I wanted to publish real journalism about the comics industry.

Gilbert: I was impressed with it because it was very scrappy.

Very, like, you know, in your face, you know, arguing about comics.

And I thought, "Well, we can take these guys' crap."

Jaime: And Gilbert goes, "I'm gonna send a copy to these guys.

Maybe they'll review it and we'll get free press or, you know, advertisement."

So, we're like, "OK, OK, cool."

And then he mailed it off to them.

We didn't hear from them for like a month or something like that and we forgot about it, you know, and we just went about our business, went back to being punk, ha, and then we got a letter from Gary Groth and he said, "I love this.

I'm gonna write a review about it in the "Journal.""

Groth: When Gilbert and Jaime sent me that first issue of the comic, I saw for the first time this glimpse of what I thought comics could be, but couldn't have seen myself.

I only saw it in my mind's eye, you know.

So, I think I was probably the only one in the office who actually read the book.

So, I decided to write a review of it and it was just a two-page review with a lot of their art.

My first paragraph reads, ""Love and Rockets" is a most impressive debut of not one but two very promising young artist-writers.

There are 3 very important elements that separate this fine amateur, in quotes, effort from the galloping mediocrity littering the comic stands these days.

First, "Love and Rockets" is the work of genuine imagination; a very individual, idiosyncratic, and energetic imagination.

Second, both Jaime and Gilbert deal with ideas, not pretentious nonsense or regurgitated pulp trappings.

Finally, they've got the technical wherewithal that's always the necessary complement to the imagination."

Reynolds: Gilbert's kind of in full control and his style is pretty well realized, but the thing that Jaime brought right from the get-go was this really--you couldn't turn away from his style.

From that first issue you just see, like, oh, my God, this guy can draw.

Groth: This is just beautiful and the pacing is perfect.

He breaks up the panels appropriately.

I mean, later on, he used a more standard 9-panel grid, but here he's using different sized panels to emphasize different actions.

His command of black and white is amazing.

You can see the influences of comics, but you can also see his own sensibility permeating it.

And I offered to publish it as a regular ongoing magazine.

Gilbert: It was like, what?

What?

You know, we actually paused for a second like, "Oh, no, we're just gonna make this on our own and we're--what?"

So... Jaime: Well, I don't know.

I kind of like this DIY thing where we do everything.

We're not going anywhere.

Sure.

Ha ha!

You know, it was kind of simple as that.

It was basically overnight, you know, and he asked to do 32 more pages to add to it, and we were like, why such a fat comic?

We didn't get it.

You know.

Groth: I wanted it to stand out apart from all the other comics that were being published.

I wanted it to be an entirely different format 'cause I thought it was important enough to set it apart.

Miranda: "Love and Rockets" in many ways is worth returning to because it does, you know, you go back to the older ones and you're capturing a different spirit, a different setting.

On the left, we have the first--the real first issue of "Love and Rockets."

On the right, we have the reissue that was put out, I believe it was a couple years later.

In some ways, it captures the ways in which you would see the Hernandez brothers evolve over time, that this comic that started, you know, it starts off with a robot.

It's "Love and Rockets," it's sci-fi, it's action, it's superheroes.

By the time they did the reissue, you can tell that they're finding their own voice and that voice is not with the monsters, it's with people.

Jaime: And that's when the Hopey/Maggie thing started to blossom, where I was like, "OK, now I get to--I don't have to draw Maggie as a mechanic 'cause that story's already in there.

Now I could just have it where they're hanging out being punk kids."

Gilbert: But it was really, really on the strength of Jaime's art that really captured people's eyes.

It was mostly like mainstream artists and readers who looked at "Love and Rockets" like, "Whoa, this is the new artist.

This is the new guy."

'Cause that's how people thought about comics in those days.

And Jaime instantly became noticed because of the first issue of "Love and Rockets."

Hall: Jaime will actually start off with this grid of panels and start drawing things in and writing things in organically, sort of as a holistic approach to the comics page.

He thinks in comics.

He doesn't translate scripts into comics, he thinks originally in comics.

This page is really quite remarkable because if you notice, it's in Jaime's traditional 9-panel grid, but it's wordless, and-- but he's establishing the entire thematic meaning of the story in this really elegant, formal composition.

So, what you've got is you've got--you can look at this as a series of panels going in a X format and also in a diamond format.

And if you see that this diamond shape, all the panels in this diamond shape are Izzy writing, and this sort of process of writing and the real pain and the sort of tortured catharsis that is involved with her writing about her past and about her sins.

And then the cross shape is actually the sins themselves.

So, this is referring to a broken marriage.

So, it's a divorce.

This is about a getting an abortion and this is about having conflict with her father, with her parents, and this is about an attempted suicide.

So, these are the sins that Izzy is dealing with and that she has to confront when she goes down to Mexico and confronts the devil.

So, it's this really incredibly elegant way to start an entire story in this wordless composition that establishes the themes for the entire story moving forward, which then begins and has the sort of official first page here--"Flies on the Ceiling.

The story of Isabel in Mexico."

It's one of the most sophisticated uses of surrealism, I think, ever in any medium.

Kovinick Hernandez: I studied photography in school and this was at the time when the comic first came out and they needed photos.

So, we would just take, like, a picture of a band and they're posed like this and, you know, they're kind of dressed up cool or whatever they like, and that's what we thought, you know, you do for photos.

The first photo shoot we did, it was in an alley and it was Mario and Gilbert and Jaime.

And they were just kind of posing, you know, I guess it looked like a band picture and stuff and some people, he said, were just like, "Oh, what are they doing?"

They'd pose funny or just serious and just have fun.

♪ Groth: It felt like it was us against the world, you know?

We were establishing this beachhead of a truly alternative vision of what comics could be.

Jaime: And then I remember Gary goes, "So, what about a second issue?"

And that one took a while because we were so untrained and instead of, like, freaking out and running away, Gilbert and I were like, "OK, we gotta be professional.

We gotta be--do this."

Gilbert: Second issue came out and Jaime exploded.

He changed comics forever.

He had the good dinosaur cover but he had this long Maggie story, you know, that was an adventure story where they're out in the jungle and there's a dinosaur and a rocket ship and all this crazy stuff going on, but he really put himself into it.

He put so much of himself into that that it just, like, it rocked comics.

That's when Marvel started calling.

Jaime: All these big shots, and are like, "Hey, why don't you come to DC?

Hey, why don't you come to Marvel?

You could do yourself a big favor, you know, by coming to us."

Gilbert: We're into punk.

We didn't care about how they wanted us to make it.

We wanted to do it on our own.

♪ Reynolds: Jaime's very early on dialed in on Maggie and Hopey.

Maggie and Hopey were the constant for the first several years of the series.

Over time, Maggie really became the heart and soul of Jaime's stories.

Jaime: "Love and Rockets" for me basically is this girl-- Maggie.

♪ Maggie is usually not a nervous person but kind of not always sure of herself.

So, she always has this guarded posture.

Kind of like she's camera shy, you know.

I have to admit sometimes it's hard to get her to-- what she's gonna wear.

I'll put her in a coat.

Maggie's had her look for years, so, she's easier to figure out.

After her punk days, she's pretty much a dorky dresser.

I mean, there's nothing fancy about her, nothing like the latest styles or anything.

She's wearing jeans.

When it comes to inking it, that's when I get to straighten out the face.

It's a lot harder to draw someone that is getting older and getting wrinkles before they're very old.

So, it's really difficult to make a 50-year-old or a 60-year-old Maggie.

Let's see.

And her left foot.

She's got a brace.

'Cause in the past she's had trouble with this ankle.

And I've written stories about it.

But I still never have said exactly the reason why, how she got it.

Well, she hurt her foot when she was younger and never got it treated.

So, it flares up every once in a while and now that she's older, it flares up even more.

And she told everyone that--she just said, "I hurt it when I was little."

But I want to write a story about it, but I still don't know what the secret is of why she really did it and that she won't tell everybody.

That's it.

It's just life following Maggie to where she was what, 20, here?

And now she's almost 60.

You know.

Miranda: You can see the progression of how the characters have evolved physically over time.

One of the things that makes their comic books so compelling is that these are never static people.

These are people who age, they gain weight, they lose weight, they change their hair.

It's just great to feel that they evolve like real people.

Reynolds: And I feel like the series, you know, is maturing in real-time with me.

Like, as I get older, the stories just become that much more resonant because I recognize myself in the younger characters but also in the way that they've aged, for better and for worse.

I love this.

Just beautifully composed covers.

Really underscores just what a brilliant cartoonist Jaime is in the way that he can telegraph age in real time.

I think that's like a--almost like a superpower that Jaime has because how on Earth you draw a character aging in real time and showing the effects of age from issue to issue, from year to year, from decade to decade, and doing it just so organically in a way that you don't even notice.

It's like strange magic to me.

I love this, too, you know, 20-something, hanging out in the bar, drinking beer.

Here it's 2016 and they're showing each other cat pictures on their phone.

Miranda: The way in which they represent women has such been-- has been such an archetypal shift from the ways in which women are typically depicted in comics.

And then here, I think this comic also gets at to why these comic books have remained relevant for so long and I think why they get their female characters so right.

After the punk reunion at the club where Maggie and Hopey are reunited with all of their friends, they all go to a diner and then they start having a conversation about menopause.

Who's getting their periods, who isn't getting their periods.

It's a quick aside that takes place over a couple of panels, but it feels so real because what kinds of conversations are women this age having?

They're talking about their bodies, they're talking about entering menopause.

And for me, this is a surprising thing to see in a comic, especially one written by men.

Menopause is not something that's talked about very much and it's the sort of thing that really makes me appreciate "Love and Rockets," that they go there.

Gilbert: We grew up with my grandma and my mom raising us and my mom had sisters around town and whenever there was a family gathering is always the matriarchs, all the women together, were who ran things.

Which was good about that, that there was no machismo about it.

It was all laughing and cooking and playing with the kids and, you know, arguing and drinking and, you know, it was everything.

It was like the world.

Miranda: That layered experience of the female experience all the way from our bodies to our psychology, and over the period of time that they've done it, I mean, I can't think of another comic book that has done this so profoundly and at the time that they were doing it, because it was truly prescient.

Karen Tongson: What you get is that kind of deep core sense of friendship and trust between the female characters, and that extends from sexual intimacy to other kinds of closeness.

And I think that that's part of the range of emotion that one can expect from the series and why it's so popular, especially with female audiences and with queer audiences.

Hall: "Love and Rockets" represents this really remarkable moment in terms of representation of queer identities in comics.

"Love and Rockets" is one of the first very powerful and profound representation of queer people in American comic books.

Jaime and Gilbert do not identify as queer themselves but they are incredibly good storytellers that have clearly done the research, have clearly spent a lot of time with queer people, getting their stories and getting their authentic narratives and turning these into comics.

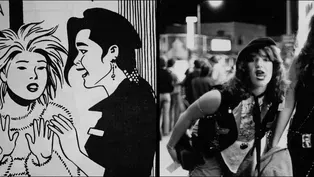

This is this kiss that really changed the comics of American comics world in a lot of ways because it was one of the first and most profound examples of two women kissing.

You see this right here and sort of origin story of their relationship.

This is where Hopey is very much identified as a lesbian.

Maggie's more sort of bisexual and a little bit more unsure about her own sexuality.

But here, Hopey going, "Aah!

That's why I love you so much!

You're such a weirdo!"

And Maggie says, "Hey, don't grab my--hey, stop!

Hopey!

Hopey, what are you...?"

And there's the kiss.

And then Hopey says here, "Are you mad?"

"No, just..." And this is such an elegant, beautiful description of a-- of the first time for someone to have a queer experience where clearly--and Hopey's done this before.

She is very much identified as a lesbian.

But this is new for Maggie.

And this--it's just a couple of words and it's really what's unsaid that really nails this moment.

This was the first time that I would say the majority of American comics readers actually got a chance to see this.

So, incredibly important.

It's very, very important to have queer women depicting themselves but it's also important to be able to have representation that moves beyond these extremely marginalized communities and into the mainstream in some way.

As much as "Love and Rockets" really represented that.

Tongson: What you get in "Love and Rockets" is an honest portrayal of the presence of queer people.

And sometimes, they're not main characters.

Sometimes, they're side characters.

And I think it also attests to the diversity of a kind of SoCal milieu, where there are a bunch of folks, queer of color, of color but not queer, who get together and go to house parties and experience life together.

♪ Reynolds: As Maggie's gotten older, become less about the lives of disaffected youth and more of a picture of life in a more broader holistic kind of sense.

You can't sustain living like a 22-year-old for 40 years.

You have to evolve or die.

And Jaime, as you know, has evolved better than any cartoonist that I can think of.

I really think Jaime is probably the greatest living cartoonist we have today.

♪ Groth: We only started Fantagraphics 6 years before we started publishing "Love and Rockets," so, "Love and Rockets" spans the majority of Fantagraphics.

The majority of my professional relationship with comics.

And it really spans the history of this era in comics.

And, of course, Gilbert and Jaime have become two of my best friends in comics.

So, it's just been a great and rewarding journey to be involved with them personally and professionally and to be given the responsibility of putting their work out in the public.

Certainly one of the highlights of my life and my career.

♪ Kovinick Hernandez: The comics world is not an easy business to make a living.

You know, you could work in comics but still, it's not like you're getting the salary you deserve a lot of times.

Gilbert and Jaime are really lucky that they can do whatever they want with their books as far as timing and stuff and that they get to do this still to this day.

Esther Claudio Moreno: They had to stay true to themselves and that's something that I have spoken about with many artists all over the world.

How the Hernandez brothers were an inspiration for them to believe that they could tell their own stories and that they could create whatever they wanted to create.

Hall: And this sort of-- the gravitas of this profound achievement and experimentation in comics form transformed everything.

It showed us possibilities, right?

Not that every creator is gonna have the wherewithal to actually do something like what they do, but they showed us that it was possible.

Reynolds: "Love and Rockets" just showed the art form of comics could do anything and just pioneered things in really a whole number of ways.

Miranda: There is this incredible body of work but is it as high-profile as it deserves to be?

♪ Reynolds: It was really "Love and Rockets" that put not only Fantagraphics on the map but alternative comics on the map.

Groth: You're talking about a body of work that's thousands of pages long.

It's just an astonishing achievement partly because of the sheer quantity of it, but mostly because of the quality.

It's never flagged.

It's consistently good.

And maybe more than that.

♪ Jason Schnittker: The Hernandez brothers created their own universe and it's been going on for many, many years.

It's an extraordinary commitment to craft and to artistry and narrative.

I'm happy to have met them briefly and it's a wonderful contribution to comics and also just to fiction more generally.

♪ Reynolds: I can't envision those guys ever wanting to stop.

They're gonna stop when forces outside their control make them because if it's up to them, they'll keep doing it forever.

Groth: In a lot of ways, they've gotten better over the years.

They have continually pushed themselves creatively.

Greg Wong: Those bros Hernandez, who are, like, so much to people like me.

You know, they were Los Angeles.

They're comic books.

They're punk rock.

They're do it yourself and just amazing.

Jaime: People ask me, "When do you think you made it?

What was the time you thought you made it?"

And I go, "When we did that first one that we put on the couch."

♪ There's a point while you're making the comic, going, "I don't want to do this anymore.

I'm tired.

This is really--" and then when you're done with an issue, you go, "Oh, God, it's done, but it wasn't that good.

I have to make the next one better."

But, you know, in the end, I'm happy to do it.

The rewards are so much more fun than not doing it, I guess.

I don't know what life is gonna be not doing "Love and Rockets."

♪ Announcer: This program was made possible in part by a grant from Anne Ray Foundation, a Margaret A. Cargill philanthropy; the Los Angeles County Department of Arts & Culture; the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs; the Frieda Berlinski Foundation; and the National Endowment for the Arts, on the web at arts.gov.

The Authenticity of Love & Rockets’ Women Stories

Video has Closed Captions

“Love and Rockets” broke ground in American comics with its queer and female narratives. (3m 27s)

L.A.’s Punk Rock Scene in Love and Rockets

Video has Closed Captions

“Love and Rockets’" punk-forward storylines have roots in L.A.’s punk rock scene. (8m 48s)

Love & Rockets (Extended Preview)

Video has Closed Captions

A self-published comic book made by brothers from Oxnard, Ca. makes comic book history. (1m 52s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipArtbound is a local public television program presented by PBS SoCal